Responsible Sass Authoring

In capable hands, Sass can do amazing things for your CSS. With Sass, you can use functions and variables that later get compiled into valid CSS. This can greatly reduce code repetition and the potential for mistakes.

For example, not that you would, but you could write some Sass like this:

// Set a couple of vars

$titleColor: #000

$titleSize: 24px

.article

.title

color: $titleColor

font-size: $titleSize

.alt-title

@extend .title

border-bottom: 1px solid lighten($titleColor, 80%) // #ccc

color: transparentize(lighten($titleColor, 20%), 0.1)

.sub-title

@extend .title

font-size: round($titleSize * 0.85) // 20.4px

&:hover

background-color: transparentize(change-color($titleColor, $red: 255), 0.8);

The resulting CSS might look something like this, depending upon how you set your Sass output style preference:

.article .title,

.article .alt-title,

.article .sub-title {

color: #000;

font-size: 24px;

}

.article .alt-title {

border-bottom: 1px solid #cccccc;

color: rgba(51, 51, 51, 0.9);

}

.article .sub-title {

font-size: 20px;

}

.article .sub-title:hover {

background-color: rgba(255, 0, 0, 0.2);

}

Pretty cool, right? You can see that the @extend keyword can be a very

powerful tool, bringing a quasi-object-oriented paradigm to our CSS. The same

could be true for the nested selectors; you just have to refer to .article

once, and let the indentation take care of the scope for you.

CSS Bloat

Over a year of using Sass every day at my day job has taught me this: Just because Sass allows you to do something, it doesn’t mean that thing should be done.

Sass clearly offers many ways to make our lives easier as developers. The

benefits of using it are obvious and many. @import is awesome; it lets us

concatenate many development Sass files into one production CSS file if we

wish. Variables and mixins can be amazingly handy.

Selector nesting, @extend, and parent-selector (&), while incredibly

useful when care is taken, can also be prone to generate sub-optimal CSS when

used carelessly, especially in cases where they are used in combination.

Long-term, CSS that is compiled from Sass that abuses these features can

quickly become extremely bloated and challenging to maintain. Let’s take

a look at some examples of some really sad CSS. The examples I’m using are

inspired by actual projects I’ve worked on (with some key edits to protect the

innocent).

Note that I’m not blaming Sass itself for any of these problems. It’s quite simply that using some Sass features in a certain way can inadvertently amplify poor CSS design decisions.

Case 1

Sass selectors that are nested like this:

#product

.overview

.header

h2

span

.content

.promo

.header

div

.inner

a

span

will result in CSS descendant selectors that look something like this:

#product {}

#product .overview {}

#product .overview .header {}

#product .overview .header h2 {}

#product .overview .header h2 span {}

#product .overview .content {}

#product .overview .content .promo {}

#product .overview .content .promo .header {}

#product .overview .content .promo .header div {}

#product .overview .content .promo .header .inner {}

#product .overview .content .promo .header .inner a {}

#product .overview .content .promo .header .inner a span {}

Yuck. I’m not going to go into why this is bad, but you don’t have to take my word for it; simply google “CSS performance descendant selectors” and read up.

With Sass, this kind of CSS bloat is extremely easy to cause if you get carried away with selector nesting. Observe the redundancy and the verbosity of the generated CSS. If the developer had taken the time to carefully construct his selectors, he could have avoided the need for this many levels of descendants in his CSS.

To my great shame, that developer was yours truly.

Case 2

This one combines the @extend, nesting, and parent-selector features of Sass.

@extend has been one of my favorite features of Sass ever since it was added.

It lets you inherit the properties of one selector in another. Here’s how it

can go awry, despite all the best intentions. The Sass:

.clearfix

&:after

clear: both

content: '.'

display: block

height: 0

line-height: 0

overflow: hidden

width: 0

.thing-1

@extend .clearfix

.thing-2

@extend .clearfix

// ...

.thing-99

@extend .clearfix

.thing-100

@extend .clearfix

In the Sass, let’s assume I extended .clearfix in 100 separate selectors at

various places throughout my code. This is, unfortunately, a very realistic use

case for something as commonly used as a clearfix, and as my project grows, it

would eventually result in the following generated CSS:

.clearfix,

.thing-1, .thing-2, .thing-3, .thing-4, .thing-5,

.thing-6, .thing-7, .thing-8, .thing-9, .thing-10,

.thing-11, .thing-12, .thing-13, .thing-14, .thing-15,

.thing-16, .thing-17, .thing-18, .thing-19, .thing-20,

.thing-21, .thing-22, .thing-23, .thing-24, .thing-25,

.thing-26, .thing-27, .thing-28, .thing-29, .thing-30,

.thing-31, .thing-32, .thing-33, .thing-34, .thing-35,

.thing-36, .thing-37, .thing-38, .thing-39, .thing-40,

.thing-41, .thing-42, .thing-43, .thing-44, .thing-45,

.thing-46, .thing-47, .thing-48, .thing-49, .thing-50,

.thing-51, .thing-52, .thing-53, .thing-54, .thing-55,

.thing-56, .thing-57, .thing-58, .thing-59, .thing-60,

.thing-61, .thing-62, .thing-63, .thing-64, .thing-65,

.thing-66, .thing-67, .thing-68, .thing-69, .thing-70,

.thing-71, .thing-72, .thing-73, .thing-74, .thing-75,

.thing-76, .thing-77, .thing-78, .thing-79, .thing-80,

.thing-81, .thing-82, .thing-83, .thing-84, .thing-85,

.thing-86, .thing-87, .thing-88, .thing-89, .thing-90,

.thing-91, .thing-92, .thing-93, .thing-94, .thing-95,

.thing-96, .thing-97, .thing-98, .thing-99, .thing-100 {}

.clearfix:after,

.thing-1:after, .thing-2:after, .thing-3:after, .thing-4:after, .thing-5:after,

.thing-6:after, .thing-7:after, .thing-8:after, .thing-9:after, .thing-10:after,

.thing-11:after, .thing-12:after, .thing-13:after, .thing-14:after, .thing-15:after,

.thing-16:after, .thing-17:after, .thing-18:after, .thing-19:after, .thing-20:after,

.thing-21:after, .thing-22:after, .thing-23:after, .thing-24:after, .thing-25:after,

.thing-26:after, .thing-27:after, .thing-28:after, .thing-29:after, .thing-30:after,

.thing-31:after, .thing-32:after, .thing-33:after, .thing-34:after, .thing-35:after,

.thing-36:after, .thing-37:after, .thing-38:after, .thing-39:after, .thing-40:after,

.thing-41:after, .thing-42:after, .thing-43:after, .thing-44:after, .thing-45:after,

.thing-46:after, .thing-47:after, .thing-48:after, .thing-49:after, .thing-50:after,

.thing-51:after, .thing-52:after, .thing-53:after, .thing-54:after, .thing-55:after,

.thing-56:after, .thing-57:after, .thing-58:after, .thing-59:after, .thing-60:after,

.thing-61:after, .thing-62:after, .thing-63:after, .thing-64:after, .thing-65:after,

.thing-66:after, .thing-67:after, .thing-68:after, .thing-69:after, .thing-70:after,

.thing-71:after, .thing-72:after, .thing-73:after, .thing-74:after, .thing-75:after,

.thing-76:after, .thing-77:after, .thing-78:after, .thing-79:after, .thing-80:after,

.thing-81:after, .thing-82:after, .thing-83:after, .thing-84:after, .thing-85:after,

.thing-86:after, .thing-87:after, .thing-88:after, .thing-89:after, .thing-90:after,

.thing-91:after, .thing-92:after, .thing-93:after, .thing-94:after, .thing-95:after,

.thing-96:after, .thing-97:after, .thing-98:after, .thing-99:after, .thing-100:after {

clear: both;

content: '.';

display: block;

height: 0;

line-height: 0;

overflow: hidden;

width: 0;

}

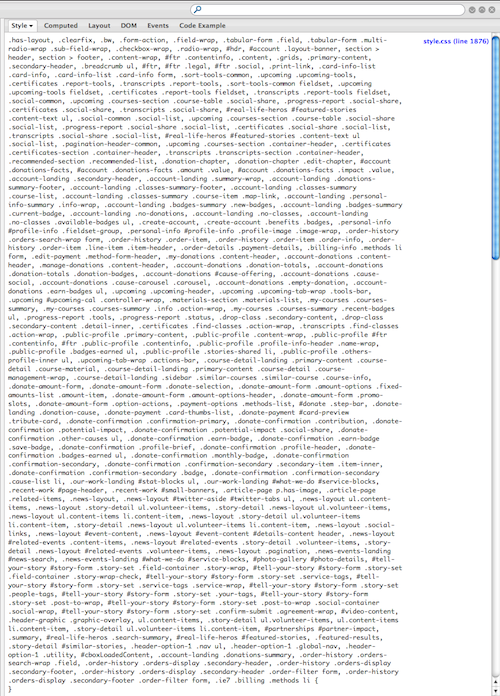

First, there is a nesting issue. Because I nested &:after inside an empty

parent selector, the generated CSS contains a huge list of selectors with no

properties, then a second huge list with the clearfix styles. Plus, all these

bogus selectors tend to clog up dev tools like Firebug, as shown in this

screenshot:

Secondly, this could have all been avoided if I had been more pragmatic and

simply used .clearfix (or another class – I commonly use .group) in

the HTML to apply the CSS and make it semantically meaningful at the same time.

Using @extend is not the correct choice for this particular pattern:

.group:after

clear: both

content: '.'

display: block

height: 0

line-height: 0

overflow: hidden

width: 0

// That's right, I'm not using @extend here.

// It's almost as if I'm using actual CSS \o/

<div class="thing-1 group">

<!-- stuff floated left -->

<section class="primary-content">

<!-- ... -->

</section>

<!-- stuff floated right -->

<aside class="secondary-content">

<!-- ... -->

</aside>

</div>

Sass => CSS

I, for one, side with those who seek to balance CSS performance concerns with maintainability concerns. It’s important to remember that no matter what you do in Sass, it will eventually end up as CSS. Whether it does more harm than good will be up to you.

Ironically, though it might seem at first that we have veered too far towards the maintainability side of the spectrum with our CSS, it turns out that the status quo isn’t terribly well suited for either maintainability or performance.